I firmly believe that had Caesar Hull served throughout the war he would be spoken of in the same breath as South African leaders in the RAF such as Malan and Hugo.

After Caesar’s death John wrote:

“For two days I have been thinking of Caesar. I loved him as I would a brother. He was more than a rare person in the RAF, and there can never be anyone to replace him in character, charm and kindliness. We came to 43 (Squadron) together and grew up in it together. We knew each other from A to Z and it is a privilege no one else could share…He had a good life and I think that he loved every minute of it. I never heard anybody say an unkind thing about Caesar and I never heard him say an unkind thing to anybody else. One can’t say more than that, can one?”

These letters and their insight into one of South Africa’s aces were the inspiration for my updating the original article.

EARLY LIFE

One of the most famous of the RAF’s early fighter pilots, Squadron Leader Caesar Hull was well-known even before the start of the Battle of Britain. By the time that the pivotal conflict began, he had already seen action over Scotland and in Norway, had been awarded the DFC and received a Mention in Dispatches.

Caesar Hull was born on Leachdale Farm in Shangani, Southern Rhodesia on 23 February 1913, where his father raised cattle and grew maize, but was brought up in South Africa where he was home schooled until 1926. Caesar Hull was then a boarder at St John’s College in Johannesburg. Wynn, Mason, Collier, Wood and Dempster list him as South African. Robert Stanford Tuck, a close friend of Caesar’s from when they learnt to fly in 1935, refers to him as a Southern Rhodesian in his biography. Salt in her definitive history of the Rhodesian Air Force includes Hull in the Rhodesian Aviation WW2 Roll of Honour. She does however state that the requirement for inclusion is not necessarily Rhodesian by birth but by residence as well. Saunders in fact states that the family moved to South Africa in 1918 and became citizens of South Africa. Simpson refers to him as a South African. Townsend refers to him as husky-voiced South African.

Hull’s father served in the desert campaign in German West Africa in the First World War. In 1918 the family was farming in Nylstroom in the Transvaal, South Africa, moving in 1922 to Voeglestriuskraal, near Rustenburg. Hull and his brothers were taught at home by their parents until 1926, when they went as dayboys to St John’s College, Johannesburg. Caesar Hull was an excellent shot and a proficient boxer.

On leaving school, Hull moved to the family farm, Herefords, before moving to M’Babane, Swaziland, where he worked for a mining company.

In 1934 Hull was picked for the Springbok boxing team at the Empire Games at Wembley. After attending the Games in 1935 he returned to South Africa, spoke of his new-found love for England and was determined to go back. After returning Hull decided to join the South African Air Force. Hull joined the Transvaal Air Training Squadron Reserve. There was an initial difficulty because he did not speak Afrikaans but eventually, he became a cadet in the SAAF Reserve Training School at Robert Heights. On completion of his training course, Hull’s lack of Afrikaans prevented his transfer to the SAAF.

After being turned down by the SAAF he was accepted for a short service commission in the RAF in September 1935. Hull began his ab initio course in July 1935 and went to No 1 RAF Depot, Uxbridge on 16 September 1935. On 28 September 1935 he was posted to 3 Flying Training School, Grantham. With his training completed, Hull joined the famous 43 Squadron – the “Fighting Cock” – at Tangmere, West Sussex on 5 August 1936 as a Pilot Officer. The London Gazette has it as 29 October but misspelled his name which was corrected in the issue of 12 November 1935!

There are two dates as to when Hull quit boxing and two very divergent reasons as to why Hull gave up boxing.

Hull stopped boxing in 1936, as he feared that his ability as a pilot would be adversely affected by his boxing.

EARLY FLYING CAREER

Hull quickly established himself as a first-class pilot, flying the sleek silver Hawker Fury biplane fighters marked with black and white squares denoting 43 Squadron.

Hull became integrated into Squadron life as is illustrated in a letter from Pilot Officer John Simpson in December 1936:

“Jack Sullivan and I were promoted to Pilot Officers from Acting Pilot Officers and had to buy some champagne. We played all sorts of games and beat 1 Squadron at all of them. Caesar was at the top of his form, rolling on the floor on Johnny’s back and biting his ears!”.

Simpson in a letter in March 1937 gives insight in Hull superb flying skills:

“I have just flown with Caesar. We were meant to do some instrument flying together, taking turns to be under the hood. But of course, the moment we had taken off, we had no intention of doing anything except try to frighten each other. It was a lovely cloudless day over the Sussex Downs at about 10,000 feet. Ever since I had been there, I had felt left behind the others and have been slower in my training … particularly in landing and taking off in formation. I think I am really a little frightened. I have never admitted this to you before. But there it is. Knowing Caesar is making a difference. I can’t say why, but he seems to give me confidence.

“You see, 43 Squadron has a reputation throughout the Service for their formation flying. We tuck in so close that there are only a few inches between us … six inches is the average. After flying with Caesar yesterday my fear is almost gone.

‘He started off by doing a falling leaf in our old Hart, which I had never done before. Then he tried to do a bunt but failed. I don’t know whether you know what that is, but it usually tears the wings off the aeroplane. He was frightened the Hart wouldn’t take it.

“We did inverted spins and rocket loops, but I have confidence in him that I wasn’t frightened once. You know how he loves flying. I think it is his only Passion. Frankly, I think if he had to choose between a girl and a Fury he would take the Fury.

“I tried to frighten him when I took over. I did loops and rolls without any fear. I have always been cautious about this when Caesar was about because he is so good at it. But yesterday, those loops and rolls and spins were something to write home about.

“It is fun having him to talk shop to. When we landed we hit each other very hard on the back and he said, ‘Wizard,’ which he says to everything

Caesar and Prosser Hanks have threatened to change seats in the air, flying the same Hart. It sounds impossible and I can only hope they don’t try”

In a second letter in March 1937 Simpson boldly announces:

“Caesar and Prosser have done it! They took off in an Audax yesterday and said that they were going to change seats in the air. We were not impressed and when they landed, in different seats, we said that they must have comedown somewhere and change seats. Johnny Walker insisted they must do it again over the aerodrome to prove it. The staggered off to about 5000 feet above our heads, and from manoeuvres the plane was doing it was plain to see that they were really changing, Johnny Walker and I were rather frightened in case one of them fell out. After a while the Aircraft flew normally and landed.”

Franks gives the seat-swop aircraft as a Hawker Hart. Simpson was however an eye witness, so I am inclined to go with the Audax.

Simpson was not the only young pilot to benefit from being taken under Caesar Hull’s wing. One of the Woods-Scawen brothers, Tony also benefitted. The pilots in the Squadron, seeing a new man in the mess wearing glasses were horrified: the RAF must be scraping the bottom of the barrel. But as in his training days, Tony attracted sympathy. Two of the senior pilots, Caesar Hull and Frank Carey, took pity on this lean and patently vulnerable youth who had been thrust so mercilessly amongst them and decided to put him through his paces. Tony told his friend ‘Bunny’ Lawrence: “They have been giving me the benefit of all their terrific flying skills by taking me up for wizard dogfights and drilling me in aerobatics. I can now roll at 2-300 feet without being too scared, thanks to them, but still get plenty of frit on occasion.” This was priceless experience and the two senior pilots, for their part, were pleasantly surprised at Tony’s natural ability.

What kind of person was Caesar Hull? His friend John Simpson provided the following description in a letter dated 11 June 1937:

“You will like Caesar. His voice is odd. It’s more like a croak. As if he’s got a very sore throat. We tell him to pull his voice out of his boots. He is one of the cleanest people I have every known. Immaculately dressed. I have never heard him say a nasty word about anyone.

“He’s really a marvellous person. If there is a wet pilot in the squadron the others don’t like, Caesar will concentrate on him and help him. He’d got talent for drawing the weak chap into the Air Force picture. He is a strange mixture. Tough, as a boxer, a wonderful pilot and he is full of superstitions. He hates flies and slugs and worms. If we throw a worm at him, he just shouts, ‘Help’ and runs.

“Maybe his dislike for insects is because, while he was being born, a swarm of bees settled on the end of his mother’s bed.

We’ve got a little garden in front of our hangar and I oversee it. A few days ago, I found a worm and threw it at him. He said, ‘Right, John, you wait until I see you in the air. I’ll menace you.’

“He did the next day. I was flying by myself in the morning and he came and attacked me and did all sorts of aerobatics all around me, so close that I kept getting into his slip stream.”

Hector Bolitho, to whom John Simpson wrote the letters, also met Caesar Hull and records his impression of Caesar as follows:

“Caesar was a South African, but his energies were controlled by a tenderness of heart which might have emerged from an old, rather than a young civilisation. His face was so lively with laughter and intelligence that one did not realise for a long time it was very average as far as features go. He moved very quickly as if accustomed to flying, he was rather impatient with the slow tempo of his feet. Like most of the pre-war pilots who loved the service he had little beyond the Air Force. Girls were toys to be fondled in the back of a car but forgotten. He was married to the RAF. Caesar was a boxer, but in the rough and tumble games they played in the mess his hands were never angry. In the quiet of his room, he read serious books mostly Winston Churchill. He was a strange mixture. At night he looked beneath his bed to see if someone might be hiding there. He wore a scarf which had belonged to him from the first day he flew. He would not fly without it and one afternoon when his CO hid it as a joke, Caesar refused to go near his aircraft.”

Caesar’s piloting skills lead him to be part of 43 Squadron’s aerobatic team. Flying in a Hawker Fury, Hull represented 43 Squadron in aerobatics on 26 June 1937 at the Hendon Air Display. In spring 1938, having won three elimination bouts, Hull decided against taking part in the Imperial Championship to be held in South Africa because he did not wish for a three-month absence from 43 Squadron. The officer who took his place was killed in an airplane crash in Rhodesia. The team chosen for the May 1938 Empire Day pageant at Roborough, Devon was Pilot Officer Alan Pennington-Leigh, Flight Lieutenant APC Carver, Flying Officer Caesar Hull and Sgt Frank Carey. They made quite a name for themselves with their display.

In June 1936 the Air Ministry ordered the first 600 Hawker Hurricanes; an aircraft on which Hull was going to be considered an expert pilot. In February 1938, ‘Sandy’ Saunders the 3rd person to fly L1547, the prototype, who was now a member of 111 Squadron decided to perform his Squadron’s task of displaying the Hurricane to the other RAF squadrons by taking a Hurricane to Tangmere, home to 1 and 43 Squadrons. Everybody on the station turned out to watch him come in, including ‘Prosser’ Hanks, Peter Townsend, Caesar Hull and Freddie Rosier. At the end of Sandy’s landing run, the right undercarriage leg folded as he was turning. His audience were delighted, throwing their hats in the air. The Hurricane was not damaged, and Sandy calmly set about rectifying the situation. Still in the cockpit, he beckoned to some airmen who lifted the wing, while he pumped furiously at the undercarriage handle. Slowly the wheel came down, and, honour restored, Sandy was able to take off back to Northolt. The hydraulic system was not perfect and had got a small air-lock, a potential problem revealed for the first time by this incident. From then on a notice was fitted inside the cockpit reminding the pilot to continue pumping the handle after the green light came on showing the undercarriage was down until the undercarriage locked solid.

On 16 April 1938 Caesar Hull was promoted from Pilot Officer to Flying Officer.

After the Munich Conference in 1938, according to Peter Townsend:

“We might have found something to laugh at in the lamentable shortcomings of our equipment, but the atmosphere was too heavy with anxiety and depression for that. The older officers who had already seen one war sat with their heads in their hands repeating the fervent hope that they would never see another. Only Caesar Hull longed to have a ‘crack at the Huns.’”

In late 1938 43 Squadron was re-equipped with Hurricanes. At the outbreak of the war Hull was commanding ‘A’ Flight.

On 2 March 1939 Caesar Hull was promoted from Flying Officer to the acting rank of Flight Lieutenant.

When war was declared on 3 September 1939, it is recorded that Caesar was seen jumping up and down in the officers’ mess shouting “Wizard, Wizard!” Simpson’s letter of 3 September 1939 adds some more colour to the happenings in the Mess that day:

“We were all in the mess when the news came through. We were drinking beer. Caesar said something about old Umbrella Chamberlain and that we had to admire the organization of the Germans in the way they have gone into Poland. He says we will lose for certain if we are governed by people like umbrella Chamberlain who believe the tanks and guns that go down Wilhelmstrasse are really made of cardboard and thin plywood.” Simpson confirms Hull was dancing a jig whilst shouting “Wizard.”

HULL GOES TO WAR

The pilots would never have believed that their first combat would be against their own side, in a manner of speaking. In the days after the conflict was declared, strong winds caused several barrage balloons to snap free of their mooring lines and drift dangerously across England. 43 Squadron was sent to shoot them down. Peter Townsend, Caesar Hull, Flying Officer William Wilkinson and Sergeant James Hallowes all brought one down. Hull’s was the most spectacular by all accounts as it erupted in flames rather than merely deflating.

The Squadron’s move to Acklington near Newcastle-on-Tyne on 18 November 1939 seemed to take them further away from the any potential action. It is worth mentioning that at this early stage of the war any threat of action from the air would have to come across the North Sea from northern Germany, with France to the south still untouched by German ambitions. Thus 43 Squadron was very much in the potential firing line.

During the Phoney War there were several accidents where the pilot had forgotten to lower the undercarriage whilst landing. There is that famous scene in the film “Battle of Britain” where the OC fires a flare mid conversation to warn a pilot of this exact event. 43 Squadron CO, Squadron Leader George Lott, issued a stern warning that such mishaps would no longer be tolerated. Later that same day, several pilots, including the CO, were standing outside the flight hut when Caesar Hull was seen coming in to land. His flaps were down but not his undercarriage. Just as the Hurricane seemed about to touch down, he gunned the motor and roared past the assemble group, cockpit hood open, giving a vigorous ‘Agincourt salute’ as he did so, and no doubt grinning broadly under his oxygen mask. In such moments Hull was irrepressible.

Shortly before the end of the year, 152 Squadron, which was also based at Acklington, began exchanging its Gladiators for Spitfires. Caesar Hull and Peter Townsend decided it was an opportunity to try out the new fighter and the CO of 152 acquiesced. Although neither of them had flown a Spitfire before, both roared off into the sky and once comfortable, decided to beat-up the airfield. Coming down in a steep dive the pair, in full view of everyone, pulled their Spitfires into a perfect loop and roll – in formation. Not that they were novices at this game. They had already become an unofficial aerobatic team, with Peter leading, Caesar on the right and Frank Carey on the left. They would often slip away together in their strictly forbidden aerobatic squad.

At this stage the Luftwaffe were snooping around off and over the east coast of England checking on the weather, looking for shipping to attack, and generally observing how the RAF reacted.

On 29 January 1940 Hull had his first taste of real action. Hull was flying south-east of Hartlepool in Hurricane I L1744, with Pilot Officer Harold ‘Knockers’ North and Sergeant Frank Carey at 09:45. They spotted a He 111 bomber from 6/KG 26, but the enemy crew saw the danger and slipped into cloud. As Hull began to follow, his Hurricane was hit by a single bullet from the rear-gunner, but it did no serious damage. Simpson in a letter dated 30 January 1940 stated that Germans had claimed to have shot down Hull’s aircraft. Townsend also mentions that the Germans claimed to have shot down the Hurricane.

On 30 January 1940 at 9:45 Hull had his first success when he shared in the destruction of a He 111 with Sgt F R Carey 5 miles east of Coquet Island. The He 111 was He 111H-2 1H+KM of 4./KG26. The aircraft was piloted by Feldwebel Helmet Höfer, who was lost with his crew. Townsend gives the time as “in the afternoom”. He also states:

“All Caesars wild excitement could not conceal that he was shaken too. He had never killed in his life before. Now he had killed four in a single blow.”

This was 43 Squadron’s first kill.

The night of 30 January 30, 1940 saw three Flight Lieutenants of No. 43 Squadron, Peter Townsend, Caesar Hull and John Simpson launch into a wild near-by-hysterical jig, La Cachita, a cross between a rumba and an apache dance, which sent chairs and tables flying. Their manic elation was understandable: each man had that day shot down the first three Heinkel bombers to crash on English soil. They had killed and lived to tell the tale.

Simpson wrote that Hull took the La Cachita concept even further:

“…Caesar invented a La Cachita attack in the air. He calls out La Cachita over the R/T to Peter and follows with a noise like a machine-gun. Then Peter calls back, Himmel, Himmel ! Achtung ! Schpitfeur. Then they make an astern attack in echelon with three aircraft. They each come down and take on their opposite number. It is wonderful listening to it over the R/T. Caesar makes it all sound very exciting with his La Cachita nonsense.”

Simpson, in the same letter, also gives us insight into Hull’s religiousness:

“Caesar is slightly religious. He always says his prayers and I think he would like to sing hymns but has no ideas of being in tune, which is extraordinary because he has such rhythm in his flying. I admire so much about this side of him … I mean saying his prayers. When we were in camp at Watchet, we shared a room. After he had done all his little fusses, like looking under the bed and in the cupboard, he just laughed and told me to look under mine. “You never know there might be some feeneys about.” Then he knelt by the side of his bed and said his prayers.”

On 3 February 1940 Hull damaged a He 111 off Farne Island at 9:40. Hull was leading Red Section consisting of F/O Carswell and P/O North. They were patrolling off Farne Island where a II Gruppe He 111 was encountered. The He 111 was chased into cloud, and only a damaged could be claimed. The bomber returned to base 35% damaged.

During this lull in action John Simpson, Peter Townsend and Caesar Hull went to see “The Importance of being Earnest.” They walked back to hotel with John Gielgud and had dinner with the company.

On 21 February 1940 John Simpson crashed and hit a haystack. He managed to crawl out of his aircraft and crawl to a road before passing out.

“I came to just before they found me – Caesar and Eddie – it took a long time. Caesar’s first remark was, ‘God, he’s alive. John, you twirp. I thought you were dead. I’ve just been to your room and pinched your electric razor!’ They were sweet to me and helped me then and helped me to the car and sick quarters.”

In early March 1940 43 Squadron was moved to patrol over the Orkneys and help protect the fleet at Scarpa Flow. It was a dull business as the Germans held back and did not take advantage of the target for some time.

On 28 March 1940 Hull shared in the destruction of a He 111 8 miles off Wick at 12:30. The plane was He 111 P4+BA of Korpsführungskette/Flgkps X.

On 10 April 1940 Hull once again claimed a shared in the destruction of a He 111 of 3(F)/Obdl. with 2 other Pilots near Ronaldsay Island. Foreman records no claim by Hull or 43 Squadron on this day. However, Peter Townend wrote down what happened for John Simpson:

“It was afternoon of a lovely day, April 10. The sky and sea were very blue. There were scattered clouds and isolated rain storms which would give very little cover to a snooper. Caesar’s flight were released from duty and he and some officers were playing tennis. My flight were at 30 minutes notice and were the last of the five flights available for action. So I went into town with Eddie to do some shopping.

“The siren sounded, just as we were buying some things. We ran to the aerodrome which was a mile away, arrived at our dispersal hut, hot and flustered. Much to my annoyance we found our flight (B Flight) had only 3 serviceable aircraft.

“Then Caesar arrived, with some others in his flight (A Flight). They were still wearing their tennis kit, shirts, flannels and rubber shoes. There were only a few of their pilots as the others had gone off for the day. It was a case of my flight having the pilots and their flight having the machines. After a rather heated discussion we arranged a compromise.

“As we flew out over the Islands, we saw one Hun. We gave the Tallyho in one bellow, over the R/T. The Hun might have heard us, he turned steeply and made for a small bank of cloud.

“George Lott got there first and gave him a burst before he got into the cloud. The Caesar showed his independence. He opened his throttle full out and drew away from me. He then tore into the Hun who was dodging in and out of cloud. Now it was a matter of each man for himself. After a few near collisions, we told the boys not to fire anymore because he was finished.

“Caesar and I flew in close to him, one on each side and I could see the horrible mess in the rear cockpit. It was a beastly sight. But we were elated then and did not see it that way.”

Townsend and Hull indicated to the pilot and the other two crew that were still alive to fly the 30 miles to the coast. But the Heinkel did not make it, breaking-up when crash-landing on the sea. The crew managed to scramble out. The RAF pilots radioed to get a plot, but no boat came out to rescue the crew who were seen swing backstroke towards the shore.

It is interesting to note that Peter Townsend does not describe this incident in his book “Duel of Eagles”

Norway

On 9 May 1940 Hull was posted to 263 Squadron as a Flight Commander. Hull was excited and full of his theories on how to turn out the Hun.

Within a few days the Squadron’s Gladiators were loaded onto the Aircraft Carrier HMS Furious at Scarpa Flow. HMS Furious sailed on 14 May 1940 for Norway. On arrival the Squadron stayed aboard because the airfield at Bardu Foss was not yet serviceable. On 21 May Hull led his flight off in thick weather and landed safely, although one section of 263 Squadron had to return to the carrier.

Flight Lieutenant Tom Rowland, a great friend of Caesar Hull, was excited to see that Caesar had joined him in Norway. Rowland remembers Hull as follows:

“He was the best chap I have ever met – an extraordinary skilful pilot and a lively character.”

On 22 May 1940 Hull damaged a He 111. Other sources do not have record of this claim.

On the morning of 24 May 1940 Hull shared with F/O Grant-Eade and F/O Riley in the destruction of a He 111 at Strozholmen. The He 111 was intercepted at 500 feet. Grant-Eade attacked first from the beam, then half-rolled into stern attack and silenced the upper gunner. Riley followed with a stern quarter attack, which put the starboard engine out of action. At that moment, Hull arrived and got in a burst that stopped the other engine. The He 111 was 1H+KA (WNr 2411) of Stabsstaffel/KG26 piloted by Oberleutnant Hartmut Paul who was wounded and taken POW, as were the flight engineer, Unteroffizier Gunther Eichmann and the air gunner Unteroffizier Hans Blunk. Oberfeldwebel Eduard Strüber, the observer, and Feldwebel Alfred Stock, the wireless operator, were killed.

On 26 May 1940 Hull is credited with several claims, the destruction of 2 Ju52s, the damage of a third and the probable destruction of 2 He 111s. Foreman only records claims for a single Ju52 destroyed and a single Ju52 unconfirmed destroyed at Saltdalen in the afternoon.

At 13:00 Hull, P/O Falkson, and LT Lydekker were detached to Bodø to provide cover for the retreating troops who were headed northwards away from the advancing German Forces. When they landed at their new aerodrome, they started refuelling the Gladiators with four-gallon tins. This arduous task was by no means complete when a He 111 of 1(F)122 was seen overhead. All three leaped into their cockpits. Whilst Lydekker got off safely, mud clung to the wheels of the following two Gladiators. Hull just got of the ground, Falkson crashed in N5705. Lydekker’s plane had not yet been refueled and was ordered back by Hull. Hull then went after the He 111 single-handed. Hull found the He 111 at 600 feet and delivered 3 attacks, the bomber turned south, streaming with smoke from the engines and fuselage. The Heinkel had been critically hit, and Leutnant Ulrich Meyer crash-landed the burning aircraft south of Mo. Here he and his crew were rescued by German troops.

Meanwhile Hull had broken away to attack a Ju52/3m, which he had spotted. He rapidly disposed of this second opponent, an aircraft of 1/KgzbV 106. The crew managed to bale out of the blazing aircraft which crashed at Storfjellet, Saltdal at 16:15. The Ju52/3m was Wnr. 5636.

Hull, still having ammunition left, chased a second, He 111 without success. Hull then attacked two more Ju52/3ms from 1/KGzbV 106. One of the Junkers escaped into cloud but the other went flaming down after six men had baled out. Eight more paratroops of I/FJR1 were killed in the crash. While Hull thought the other transport got away, it was also hard hit, and was already on fire. The pilot managed to reach German territory, where he force-landed. Crew and paratroopers aboard all got out safely, but the aircraft burnt out completely. One Ju52/3m was ‘BA+KH’ of 1/KGzbV 106, which crashed at Ekornes, Evensdal, at 16:30 while the second was “White 2” (Wnr. 6713) from the same unit, which crashed at Kvassteinheia, Saltdal, between 16:30 and 16:40

On his way back to Bodø Hull engage yet another He 111, and drove this off, like the first, with smoke pouring from it.

We are lucky to have Hull’s description of the day’s events which he recorded in his diary as follows:

“The Wing Commander explained that the Army was retreating up a valley east of Bobo and was being strafed by the Huns all day. Sounded too easy, so I took off just as another Heinkel III circled the aerodrome. God! What a take-off! Came unstuck about 50 yards from the end and just staggered over the trees. Jack (Falkson) followed and crashed. Saw some smoke rising, so investigated and found a Heinkel III at about 600ft. Attacked it three times, and it turned south with smoke pouring from the fuselage and engines. Broke off the attack to engage a Junkers 52, which crashed in flames. Saw Heinkel III flying south, tried to intercept and failed. Returned and attacked two Junkers 52s in formation. Number one went into clouds, number two crashed in flames after six people had bailed out. Attacked Heinkel III and drove it south with smoke pouring from it. Ammunition finished so returned to base.”

Although Hull only claimed two definite and one probable post war research would reveal that Hull had in fact shot down no less than four aircraft in one combat.

On 27 May 1940 Hull was again successful whilst operating from Bodø covering the withdrawal by sea of British and Norwegian troops. Eleven Ju 87s escorted by 3 Me 110s appeared. Hull destroyed a Ju 87 at 8:00. The 11 Ju 87Rs from 1STG 1 escorted by three Bf 110s from 1/ZG 76, appeared over Bodø and began dive-bombing radio masts at Bodøsjøen, only 800 yards from the landing ground. LT Lydekker took off immediately, but Hull and his mechanic were forced to shelter from the bombing for a few minutes before Hull could take off. Hull took to the skies in Gladiator N5635. Hull at once caught Feldwebel Kurt Zube’s Stuka, of 1./StG 1, at the bottom of its dive. Hull caused it to fall in a gentle dive into the sea, where two Bf 110s circled the wreckage. Zube and his gunner were picked up safely by German troops.

As Hull completed his attack, another Ju 87 went passed and shot up his aircraft, smashing the windscreen. At the same moment Hull was attacked from behind by one of the Bf 110 escorts, flown by Lieutenant Helmut Lent, the Bf 110 ace, and the Gladiator was hit hard. Hull managed to get back to the airfield at 200 feet but was then attacked again by the Bf 110 and crashed at Bodøhalvøya, wounded in the head and knee. N5635 has been identified by the serial number found on the wreckage. Lent logged his victory at 08:20. N5635 is listed as lost in Norway by Air-Britain’s Publication RAF Aircraft N1000-N9999. Helmut Lent later became a successful night-fighter pilot and, before succumbing to injuries following a crash in October 1944, had achieved 111 combat victories and won the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamoonds.

Once again, we have Hull’s diary to summarise the action as he saw it:

“Suddenly at 0800 hrs the balloon went up. There were 110s and 87s all around us, and the 87s started dive-bombing a jetty about 800 yards from the aerodrome. Tony’s aircraft started immediately, and I waved him off, then after trying mine a bit longer I got yellow, and together with the fitter made a dive into a nearby barn. From there we watched the dive-bombing in terror until it seemed that they were not actually concentrating on the aerodrome.

“Got the Gladiator going and shot off without helmet or waiting to do anything up. Circled the ‘drome climbing and pinned an 87 at the bottom of a dive. It made off slowly over the sea and crashed into the sea. Just as I was turning away, another 87 shot up past me, and his shots went through my windscreen, knocking me out for a while. Came to and was thanking my lucky stars when I heard rat-rat behind me and felt my Gladiator hit. Went into right hand turn and dive but could not get it out. Had given up hope at 200 ft, when she centralised, and I gave her a burst of engine to clear some large rocks. Further rat-rats from behind, so gave up hope and decided to get her down. Held off then crashed.”

Hull was thrown clear of the wreckage and lay unconscious for a while. After coming to and walking away dazed and confused he was helped to the Bodø hospital by a Norwegian. On 28 May 1940 he was sent north in a hospital ship and two days later flown back to Britain in a Sunderland Flying Boat.

The evacuation was covered by just 3 Gladiators and in June 1977 a memorial was unveiled to F/Lt Hull, P/O Falkson and Lt. Lydedder RN, the airmen involved, at Bodø Airfield.

Hull was awarded the DFC on 21 June 1940. Tuck envied Hull for this achievement. The citation for Hull’s DFC reads as follows:

“After having shot down an enemy aircraft one day in May, 1940, this officer, two days later relieved the Bodo Force from air attack by engaging five enemy aircraft single-handed. He shot down four of the enemy aircraft and damaged the fifth. The next day, despite heavy air attack on the landing ground, he attacked enemy aircraft in greatly superior numbers until he was wounded and forced to retire.” Back to Tony Woods-Scawen and the battle over Dunkirk. Ordered to protect shipping over Dunkirk 43 Squadron found themselves facing the odds of six to one on the first patrol. Tony was not the only pilot who felt half the Luftwaffe were after him. Tony could do nothing but concentrate on evasive action as one German fighter after another bored in. In those critical minutes the thoughtful friendship of Frank Carey and Caesar Hull saved his life.

BATTLE OF BRITAIN

After recuperation and leave Flight Lieutenant Caesar Hull joined what was left of No. 263 Squadron on 1 July 1940 at Drem, Scotland. The unit had been ear-marked to be the first Squadron to receive the new Westland Whirlwind day-fighter, but they took a while to arrive. Finally, the first aircraft arrived and Hull helped train the new pilots during August. Meanwhile the Battle of Britain had arrived, and the Whirlwind had proved itself unsuited to take on the Luftwaffe during the day and experienced pilots were need. Hull was ordered to re-join No. 43 Squadron which he did on 31 August 1940 to take command, whilst still a Flight Lieutenant, after Squadron Leader JVC ‘Tubby’ Badger was shot down and grievously wounded on 30 August 1940.

On 16 August 1940 the Luftwaffe mounted a determined bombing assault on Tangmere. Half an hour later the rear of this formation switch to attack the naval airfield at Gosport. (Attack in which Nicholson won Fighter Command’s only VC) Tony Woods-Scawen broke-up a sizable formation of Stukas off Selsey Bill shooting two down into the sea, but with his own radiator hit, he turned for home. He was set upon by four 109s. He was forced to crash-land, wheels-up in a terribly small space. In the crash he was thrown forward and lost three of his teeth. Tony arrived back at 43 Squadron the next day bruised and disfigured to a prodigal’s welcome. Caesar Hull, who had also lost some teeth in a crash along the way in his career, when he heard about Tony’s misfortune he sent along his spare plate. Tony taking the hint was back in action within 48 hours.

On 31 August 1940 Charles ‘Tich’ Pallister arrived at 43 Squadron. Pallister described his initial meeting with Hull:

“I waited some 20 minutes, becoming a wee bit agitated, when a flight lieutenant approached me, asking: ‘Are you a replacement pilot?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. He gave me a rather penetrating look, requested me to wait at the end of the passage while he walked to the other end and entered an office. The next thing I heard was, ‘Caesar, there is a child waiting to see you. What the hell are we being sent now? He must be of age but he looks about 14 years old!’ My guts turned over. I had qualified as a pilot and had achieved good results. What an introduction! He beckoned me to enter the office and introduced me to the Squadron Leader, newly promoted, Caesar Hull, a South African. He addressed me in a rather husky voice, which I later learnt was natural, asking me where I was from and which units I had trained at. The officer who introduced me was Flight Lieutenant Kilmartin, DFC.”

Hull went on to advise Pallister: “Tomorrow report to the operation hut ready to fly. You will be my no.2 in the first scramble and I will talk to you in the morning.” Hull then organised one of the Squadron pilots to show Pallister around and to do the necessary introductions.

The next morning, 1 September 1940, Caesar Hull searched out Pallister and made sure that he had been looked after the night before, which he had.

Hull then went on to explain to Pallister what was expected of him on his first operation. Pallister recorded it as follows:

“Caesar Hull then told me I was to be his No.2 (Red 2), a position in the formation, and then explained that, when an attack occurred, the formation would break-up, and then it was every man for himself. I could protect his rear only at the commencement of the attack, which would be ordered at the call of a radio command ‘Tally-Ho’. He concluded his remarks with the instruction that, should I be separated from the squadron as the action drifted away, I had to return to Tangmere immediately, with no hesitation. I also had to remember to jink from side to side and never fly straight and level, while keeping a good lookout for the enemy aircraft or any form of attack.”

Interestingly, after tangling with Ju 88 and Ju87’s and after ‘whirling dervish’ activity Pallister did find himself alone in the sky with two parachutes slowly descending down to the ground. Making sure he was alone, remembering what Hull had said about not hanging around, Pallister:

“Don’t hang around here! Return to Tangmere. I was on my way, jinking all over the sky, determined not to fly on the straight and level. The action was close to Tangmere so I was soon back on the ground with the other pilots.”

Tony Woods-Scawen was lost on this day whilst leading Yellow section. He had expressed a belief to Frank Carey that he could always get a Hurricane down onto the ground. It was reported by his squadron mates that they did not see him take to his parachute. It was thought that he was trying to land and save the aircraft. Two school boys had however seen the plane go down and told what they had seen many years later: “I did not see the plane attacked. But when I looked, he had just come out of the plane and they seem to fall together for a few seconds. the plane seemed to be alight and the parachute was not fully open and was flapping at 2,000 feet or less. It all happened so quickly – it was over in a few seconds.” As Hull had gained Pallister he had sadly lots Tony Woods-Scawen.

On 4 September 1940 whilst flying Hurricane I V6641 near Midhurst-Petworth at 13:20 Hull is credited with 2 probable Bf110s.

On 6 September1940 whilst flying Hurricane I V6641 he is credited with the shooting down of a Bf109 near Tenterden and ½ a Ju88 probable at 9:30. Foreman has no entry for the Bf109.

The Bf109 is quite a conundrum. Hull wrote the following to his family:

“I got my first Me109 yesterday morning, as you probably have heard by now. I got his engine, and followed him down until he crashed in a small field. The machine broke up completely, but I saw the pilot being helped away by a couple of farm hands. I don’t know how he got out, hut he did.”

Saunders gives the date as 2 November 1940 and provides the following detail:

“The lucky pilot was Uffz von Stein of 4./JG2 who put his crippled Messerschmitt down near West Hythe, Kent on 2 September 1940.”

Foreman’s authoritative work on RAF Fighter Command claims does not record a claim for Hull on the 2nd, nor for that matter does he have Hull’s Bf109’claim of the 6th.

On 4 September 1940 Hull is believed to have attacked and seriously damaged two Bf 110 in Hurricane P6641. Shores and Williams list them as probables.

On Saturday 7 September 1940 Sqr. Ldr. Hull took off from Tangmere in Hurricane V6541 (Sic) Actually V6641. Hull was shot down at 17.13 hrs by a Bf 109 whilst attacking Do17s over S.E. London. Hull was killed and his Hurricane V6541 fell at Purley High School, impacting close by the entrance to an air raid shelter. So intense was the fire, and so badly shattered was the wreckage, that Hull’s body could only be identified by the numbers on his aircraft’s machine guns.

Orphen[i] described his death as follows: “He had used up all his ammunition shooting down two Dornier17s when he spotted his companion, R. Reynell, a test pilot flying on operations. Caesar dived to distract the enemy, but both he and Reynell were killed.” Mason lists Flight Lieutenant R C Reynell as shot down by Bf109s at 17.12hrs in Hurricane V7257. He baled out but was killed when the parachute failed. Shores & Williams and Foreman make no mention of the victories Orphen mentions.

Townsend[i] differs as to the German bombers. He states that they were Heinkels from KG1. He confirms that the fighters were from JG54 commanded by Hannes Trautloft. He concurs with the flow of the action and further states that 43 Squadron lost their air of invincibility with the loss of Hull.

Frank Carey, who had been wounded on 18 August, was not able to fly but had returned to the “Fighting Cocks” and he recalls what happen on this day:

“Caesar and a number of us were sitting outside the mess at Tangmere, including George Lort, a patch over his missing right eye, just discharged from hospital and Wg Cdr Jack Borer, the Station Commander. That afternoon the squadron took off and Caesar and Flt Lt Dick Rynell were both killed.”

Franks provides some more information on the dogfight that cost Hull his life:

“In the late afternoon, the unit scrambled nine aircraft led by Caesar. It was the day the Germans made their first daylight attacks on London. The RAF pilots spotted bombers heading towards the docklands and Caesar was heard over the radio announcing the attack. He asked John ‘Killy’ Kilmartin, who was leading the rear section to ‘hit’ the German fighters. That was the last anyone heard of him. While he was going for the bombers, he was probably bounced by Bf 109s possibly from JG54 and shot down. His Hurricane V6641, was badly hit and he may have been wounded or killed in his cockpit for the machine curved away and there was no attempt to bale out.”

Hough and Richards give a more philosophical view of the day’s battle:“London the first city subjected to all-out attack yet remain unsubdued, paid the first instalment of a terrible toll on that hot September afternoon. Fate struck a cruel inconsistency. Some citizens had remarkable escapes when their houses collapsed about their ears; others fell dead in the street from a piece of falling shrapnel. It was the same in the air above. How else could the brilliant and seasoned campaigner, Caesar Hull, have been struck out of the sky by 109s over the Thames Estuary? Or Dick Reyall, who as Hawker’s test pilot, knew even more about the Hurricane than Caesar? “

Pallister mentions Reynell and Hull’s loss as being a terrible shock to the Squadron.

Flight Lieutenant Richard Carew Reynell was the Hawker test pilot.

On 8 September 1940 43 Squadron was pulled out of the battle and sent north.

The London Gazette of 13 September 1940 confirmed Hull’s promotion from Flying Officer to Flight Lieutenant effective from 16 April 1940.

I am going to leave the last words about Caesar Hull and his fellow pilots to a group of people who are often forgotten when we tell the story of the fighter pilots, the WAAF ladies who would comfort them, drink with them, and in some instances, when the pilot left his mike on, listen to them die, screaming as they burnt to death. I feel ACW Anne Turly-George is a good choice as she gives a very good insight to what it was like to be a WAAF attacked to Fighter Command, she was based at Tangmere and she knew both Caesar Hull and the Woods-Scawen brothers.

“My Sister Tig and I joined the WAAF before the war was declared and we did not take it too seriously. Even when war was declared, and we marched off to Tangmere, it was still a glorious game, and this illusion continued into the early summer of 1940.

“The Summer of 1940 found us round-eyed and very earnest indeed in the ops room manning the R/T sets. This was really exciting, and we felt part of things at last, transmitting directions to fighter pilots and logging their messages.

“Then one day Stukas came howling down at us out of the sun and, after the first stunned disbelief, we tumbled into the shelters whilst they beat and hammered us into the ground. We ascended into chaos.

‘The Squadrons thundered off the ground tirelessly. Off they pelted, day after day, those glorious, radiant boys. We were with them in sound and spirit. We heard their shouts of ‘Talley Ho!’ There was one boy who would burst into song as soon as he caught sight of the enemy and swung into attack. We only heard these private war cries when they forgot to switch off their transmitters in the heat of battle, an awful yet uplifting experience. But the feeling of lead in the stomach when they failed to return was all too familiar. There were so many. I remember when Caesar Hull was killed – we all admired him. The gay and gallant American Billy Fiske; the two Woods-Scawens, inseparable brothers, devout Catholics, charmers both – and all of them so young and well endowed, and such a wicked, wicked waste. I mourned them then, now and forever.”

Edith Kup, a plotter at Debden sums it up best:

“The fighter boys were a breed apart, sadly lost in those days, forever; and I and all who knew them were very privileged.”

Hull’s brother, Robin Yorke Hull, was killed in action in North Africa on 1st January 1942.

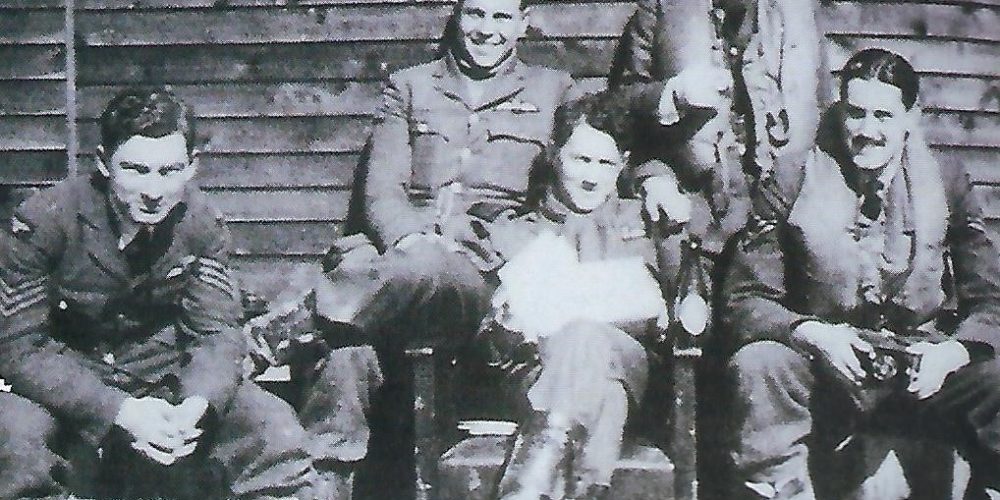

Caesar (left) with his older brother Robin.

When the news of Hull’s loss reached Southern Rhodesia, his friends and family there placed a memorial plaque alongside the main road linking the towns of Bulawayo and Gwelo, on the approach to the Shangani River Bridge. In 1986 the area had become very unstable and the plaque overgrown and untended. Hull’s family were able to retrieve it in 2004 and donate it to the Tangmere Aviation Museum.

Flight Lieutenant Caesar Barrand Hull is buried in Row 1, grave 477 at St Andrews.

A memorial to the actions of Hull, Jack Falkson and Lydekker at Bodø was built at the town’s airport three decades later, and inaugurated on 17 June 1977 with the Norwegian Minister of Defence, Rolf Arthur Hansen, in attendance.

A new monument to Hull was erected at Coulsdon Sixth Form College, which today occupies the Purley High School site, in 2013. Depicting an aeroplane and a dove intertwined, it was formally dedicated on 11 November that year, Remembrance Day, with Bryan present.

Shores and Williams give Caesar Hull’s final tally as 4 and 4 shared destroyed, 1 unconfirmed destroyed, 2 and 1 shared probables, and 3 damaged. The table below was prepared from Shores and Williams’ information.

| Date | Victories | Own plane | Location | Sq n |

| 1940 30 Jan | ½ He III H-2 1H+KM of 4/KG26 | Hurricane I L1849 | 10m E Coquet Line | 43 |

| 28 Mar | ¼ He III P4+BA of Korpsfuhrungskette/Flgkps X | HurricaNe I L1728 | 8m E Wick | 43 |

| 10 Apr | 1/6 He III of 3(F)/Obdl | Hurricane I | Near Ronaldsay Island | 43 |

| 22 May | He III damaged | Gladiator II | Barddufoss | 263 |

| 24 May | 1/3 He III of Stabst/KG26 | Gladiator II | 5m S Salangen | 263 |

| 26 May | He III unconf of 1(F)/122 which crash-landed at Mo 2 Ju52/3ms of KGrzbV 108 shot down, Ju52/3m of III/KGzbV-1 crash-landed Ju52/3m Damaged – Ju52/3m of III/KGzbV-1 force-landed He 111 damaged | Gladiator II Gladiator II Gladiator II Gladiator II | Salte Valley Salte Valley Salte Valley Salte Valley | 263 263 263 263 |

| 27 May | Ju87 of 1/StG1 crashed into the sea | Gladiator II N5635 | Salte Valley | 263 |

| 4 Sept | 2 Bf110s probables | Hurricane I V6641 | Midhurst-Petworth | 43 |

| 6 Sept | Bf109E ½ Ju88 probable | Hurricane I V6641 Hurricane I V6641 | Tenterden Tenterden | 43 43 |

HULL’S AIRCRAFT

Hawker Audax 43 Squadron RAF

Hurricane Mk I L1849 & L1728 & V6641 43 Squadron RAF. The codes change from NQ to FT in February 1940.

Gladiator N5635 of 263 Squadron during the Norway campaign. Below is HE-G/N5641.The upper surfaces are painted dark green (FS34079) and Dark Earth (FS30118) whilst the upper surfaces of the lower wings, the lower fuselage sides, and the vertical tail sides were camouflaged Light Green (FS34096) and Light Earth (FS30257). These colours produced a shadow effect compared to the upper surface colours.

A colour version of a Norway Gladiator.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Published Sources

- Barker, Ralf 1991. That Eternal Summer – Untold Stories from the Battle of Britain, Fontana, London.

- Bolitho, Hector 1943. Combat Report – The Story of a Fighter Pilot, B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

- Breffort, Dominique and Gohin, Nicolas 2010. Hawker Hurricane from 1935 to 1945, Histoire & Collections, Paris

- Bungay, Stephan, 2001. The Most Dangerous Enemy – A History of the Battle of Britain, Aurum, London.

- Cooksley, Peter, Ward, Richard and Shores Christopher 1971. Battle of Britain – Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire and Messerschmitt Bf 109, Osprey Publications Limited, Canterbury.

- Foreman, John 2003. RAF Fighter Command Victory Claims of World War Two – Part One 1939 –1940, Red Kite, Walton-on-Thames.

- Forrester, Larry 1979. Fly for your Life, Mayflower, London

- Franks, Norman 1997. Royal Air Force Fighter Command Losses of the Second World War – Volume 1 Operational Losses: Aircraft and Crews 1939-1941, Midlands Publishing Limited, Leicester.

- Friend, D G 1995. South Africans on Foreign Service, p149- 155 in Keene, John, Editor, 1995. South Africa in World War II – A pictorial History, Human & Rousseau, Cape Town

- Halley, James 1997. Royal Air Force Aircraft N1000-N9999. An Air-Britain Publication, Tonbridge.

- Harrison, WA, Greer, Don, Glenn, Darren and Gehardt, Dave 2003. Gloster Gladiator in Action – Aircraft Number 187, Squadron/Signal Publications, Carrollton, Texas.

- Hough, Richard & Richards Denis 1990. The Battle of Britain, Coronet, London

- Kaplan, Philip & Collier, Richard 2002. The Few – Summer 1940, The Battle of Britain, The Orion Publishing Group, London.

- Mason, F 1990. Battle over Britain. Aston Publications, England.

- Orpen, Colonel Neil D. 1980. Springboks on All Fronts. Reader’s Digest Illustrated Story of World War II Volume Two, Reader’s Digest Association South Africa (Pty.) Limited, Cape Town PP491-495.

- Pallister, Charles ‘Tich’, 2012, They Gave Me A Hurricane, Fighting High Limited, Hitchin.

- Salt, Beryl 2001. A Pride of Eagles – The Definitive History of the Rhodesian Air Force 1920 – 1980, Covos Day, Johannesburg & London.

- Sakar, Dilip 2010. The Few – The Story of the Battle of Britain Pilots in the Words of The Pilots, Amberly, Chalford, Stroud

- Shores, C 1999. Aces High Volume 2, Grub Street, London.

- Shores, C & Williams, C 1994.Aces High, Grub Street, London.

- Thomas, Andrew 2002. Gloster Gladiator Aces – Osprey Aircraft of the Aces #44, Osprey Publishing, Oxford.

- Townsend, Peter 1974. Dual of Eagles. Corgi Books.

- Wynn, Kenneth G. 2001. Men of the Battle of Britain, CCB Associates, South Croydon.

Magazine Articles

- Saunders, Andy 2015. “Tangmere’s Few” in Britain At War, September 2015 pp65-88, Key Publishing Limited.

- Franks, Norman 2010. “Hurricane Wizard pt1” in Flypast, February 2010 pp18-22, Key Publishing Limited.

- Franks, Norman 2010. “Hurricane Wizard pt2” in Flypast, February 2010 pp88-91, Key Publishing Limited.

Newspapers and Gazettes

- Supplement to the London Gazette, 29 Oct, 1935. Retrieved 17 May, 2016 http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/search

- Supplement to the London Gazette, Issue 34219, 12 November, 1935. Retrieved 17 May, 2016. http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/search

- Supplement to the London Gazette, Issue 34509, 10 May, 1938. Retrieved 17 May, 2016. http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/search

- Supplement to the London Gazette, Issue 34611, 28 March, 1939. Retrieved 17 May, 2016. http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/search

- Supplement to the London Gazette, Issue 34878, 21 June, 1940. Retrieved 17 May, 2016. http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/search

- Supplement to the London Gazette, Issue 34945, 12 September, 1940. Retrieved 17 May, 2016. http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/search

Internet

- Biplane Fighter Aces Website, 2003. Squadron Leader Caesar Barrand Hull DFC, RAF no. 37285, http://www.dalnet.se/~surfcity/commonwealth_hull.htm. Retrieved January 2003

- The Airmen’s Stories – S/Ldr. C B Hull, http://www.bbm.org.uk/airmen/Hull.htm. Retrieved November 2018.